By Gene Balas, CFA®

Investment Strategist

Politicians, rightly or wrongly, are often credited or blamed for things beyond the government’s control; after all, government policies or legislative acts can exert only so much influence, especially in the context of globally integrated markets and economy. Some may even attribute the current bear market or high inflation to actions taken by the U.S. government, its legislators, or leaders. Likewise, the Federal Reserve also can only affect conditions so much, given the limited scope of monetary policy.

Conclusions that U.S. political actions (or inactions, as the case may be) are a primary cause of current economic and market difficulties are difficult to prove when inflation is a global problem – hardly confined to the U.S. And that is also the case with the drop in the stock market, as markets around the world have plunged as well. Instead, there are certain extraneous (and perhaps transient) factors affecting the intertwined relationship between the stock market, inflationary pressures, and the reactions of not just the U.S. Federal Reserve, but those of central banks around the globe.

Let’s dissect each of these issues in more detail. First, as to inflation, the problem is simply that demand for goods and services of all types is simply greater than what supply can provide. Supply has been constrained by several reasons, many of which relate to the pandemic. In particular, many workers have exited the labor force, many retiring early due to concerns about health and safety, and others staying home to take care of children and other family members.

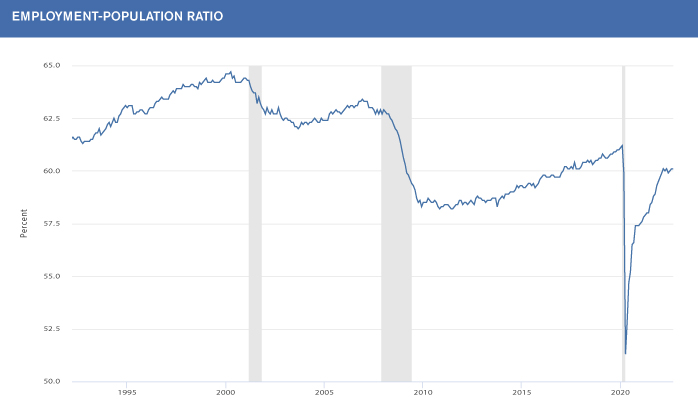

To put it simply, the pandemic has caused many people globally to rethink their priorities around work, personal life, and family obligations. When the labor force is smaller, and the supply of workers is less, then higher wages – and the inflation that results – is needed to coax more workers from the sidelines. Consider the nearby graph of the employment-to-population ratio of the U.S. over the past thirty years. Note that the U.S. has a smaller share of the population working – often due to retirement, early or otherwise – than it once had, including right before the pandemic. This is a global phenomenon, certainly not confined to the U.S.

Source: FRED

Politics can’t affect a person’s willingness to work if their life priorities have changed after the pandemic. But a reduced supply of labor around the world, coupled with strong demand globally, means that higher wages are often necessary to entice workers to join a firm to produce those goods in services. And paying increased wages often means higher selling prices and/or lower corporate profit margins.

Then we have a separate issue of global supply chain disruptions that have also contributed to high inflation by limiting the availability of finished products or components used in assembling goods in other nations. For example, China’s periodic Covid-related shutdowns of parts of its economy certainly limit the export of vital inputs needed globally. What happens in other countries is certainly outside of the U.S. government’s control.

And very importantly, there is the huge effect that the Russia-Ukraine war has had on the supply of commodities from that region. The reduced availability of Russian oil and gas to the rest of the world is a prominent example, as well as the curtailed production of other commodities, like food from Ukraine, or metals previously sourced from the region. Commodities are priced and traded on global markets – even if those commodities are produced in the U.S. or close to home, their prices still can increase.

Next, now that we’ve discussed the nature of inflation and what little any government or central bank can do in response to increasing supply, the only action to combat inflation by central banks around the world – not just the Fed – is to tighten monetary policies to tamp down demand to bring it in balance with supply. It’s also worth a reminder that the Fed (as well as most other central banks in developed nations), is independent from Federal government interference.

So, we have multiple factors that have driven down equity prices around the world; chief among them are inflation and central banks globally tightening policy to combat that inflation. Inflation can cut into profit margins if companies cannot pass along all their price increases to their customers. Higher interest rates often can make stocks less valuable, as the discounted value of those companies’ future earnings is worth less when discounted back to the present at a higher rate.

And the efforts of the Fed (and those of other central banks globally) to slow the economy to balance supply and demand to control inflation invite the possibility of a policy error and overly-restrict growth that could lead to a recession. Higher interest rates act with a lag, and it is simply impossible to know the future, and that includes seeing how rate hikes now (plus any number of other variables) will affect the economy next year.

In the meantime, investors around the world fret that shares were (or perhaps even still are) overvalued relative to these macro conditions. As a result, investors have marked down expectations of future economic growth, incorporated the effects of inflation-squeezed lower profit margins on corporate earnings, and thus revalued share prices when factoring in higher interest rates.

None of these key factors affecting the markets include political influences. And a reminder is that other countries have their own political issues as well – just ask the U.K., for example. While politicians may squabble and debate about what is the right way forward, the simple fact remains that corporate earnings and consumer spending dwarf – by far – the size of the U.S. federal budget. And those first two factors are what matters most to investors when assessing the intrinsic value of a company or the market as a whole – not political debates.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any types of securities. Financial markets are volatile and all types of investment vehicles, including “low-risk” strategies, involve investment risk, including the potential loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results. For details on the professional designations displayed herein, including descriptions, minimum requirements, and ongoing education requirements, please visit www.signatureia.com/disclosures. Signature Investment Advisors, LLC (“SIA”) is an SEC-registered investment adviser; however, such registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training and no inference to the contrary should be made. Securities offered through Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advisory services offered through SIA. SIA is a subsidiary of SEIA, LLC, 2121 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600, Los Angeles, CA 90067, 310-712-2323, and its investment advisory services are offered independent of Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. is separately owned and other entities and/or marketing names, products or services referenced here are independent of Royal Alliance Associates, Inc.