By Deron McCoy, CFA®, CFP®, CAIA®, AIF®

Chief Investment Officer

This article is an updated version of our previous article, “Negative and Less than Zero,” published in “The SEIA Report,” Q3 2019.

It’s not supposed to be like this. In normal times, if someone wants to borrow $10,000 from you for a year, you two might agree that 2% interest is the right amount for the loan, so that at the end of the year, you would have $10,200. And if the borrower asks if the loan could instead be over 5 years, you two might agree that 4% interest is a more appropriate interest rate. And you look forward to collecting twice the amount of annual interest because your money will be locked up a bit longer. Sounds logical right? It’s what we all learned in school. Yet today’s bond market is not normal and yet another sign that we live in interesting times—consider the following.

If this same scenario were playing out in today’s Europe or Japan, you would actually have to pay them the annual interest for the privilege of borrowing your money! And in the U.S. you would earn less interest for the longer loan! In short, the bond market is upside down!

Negative bond yields

Who in their right mind would pay a borrower to take a loan from them? Common logic holds that loans and bonds should not have negative yields. Truth be told, it’s a relatively new phenomenon not to be confused with “negative real yields” – where the yield on a money market fund, CD, savings account or bond would be less than the rate of inflation. In those instances, investors would lose money over time when factoring in inflation. But the yields were nevertheless still positive.

Those days now seem quaint as we now view a world of negative nominal yields. So, what exactly is a negative-yield bond? First off, contrary to the above example, it’s not a bond with a negative coupon—investors don’t actually have to pay interest to the borrower. You would still receive normal coupon payments and par value ($100) upon maturity, just as with any bond. The difference lies in what’s paid for the bond at the point of sale.

Astute bond investors know that sometimes you have to pay a premium to acquire a bond. If one-year interest rates are 2%, a one-year bond with a 2% coupon will be priced at $100. A 5% coupon bond, on the other hand, will be priced higher (around $103) in order to compensate for the extra income it provides. In essence, an investor would receive $5 in interest but lose $3 in price depreciation as the bond matures at $100. Thus, each bond pays out a net $2 or 2% return over its one-year life.

In an era of negative yields, however, the initial price of the bonds will be higher. Say an investor must pay $106 for the 5% coupon bond. They would still get their $5 in interest, but in this case, they would lose $6 in price depreciation at maturity. The investor would net a $1 overall loss on the investment, making the total yield-to-maturity -1%.

This really exists?

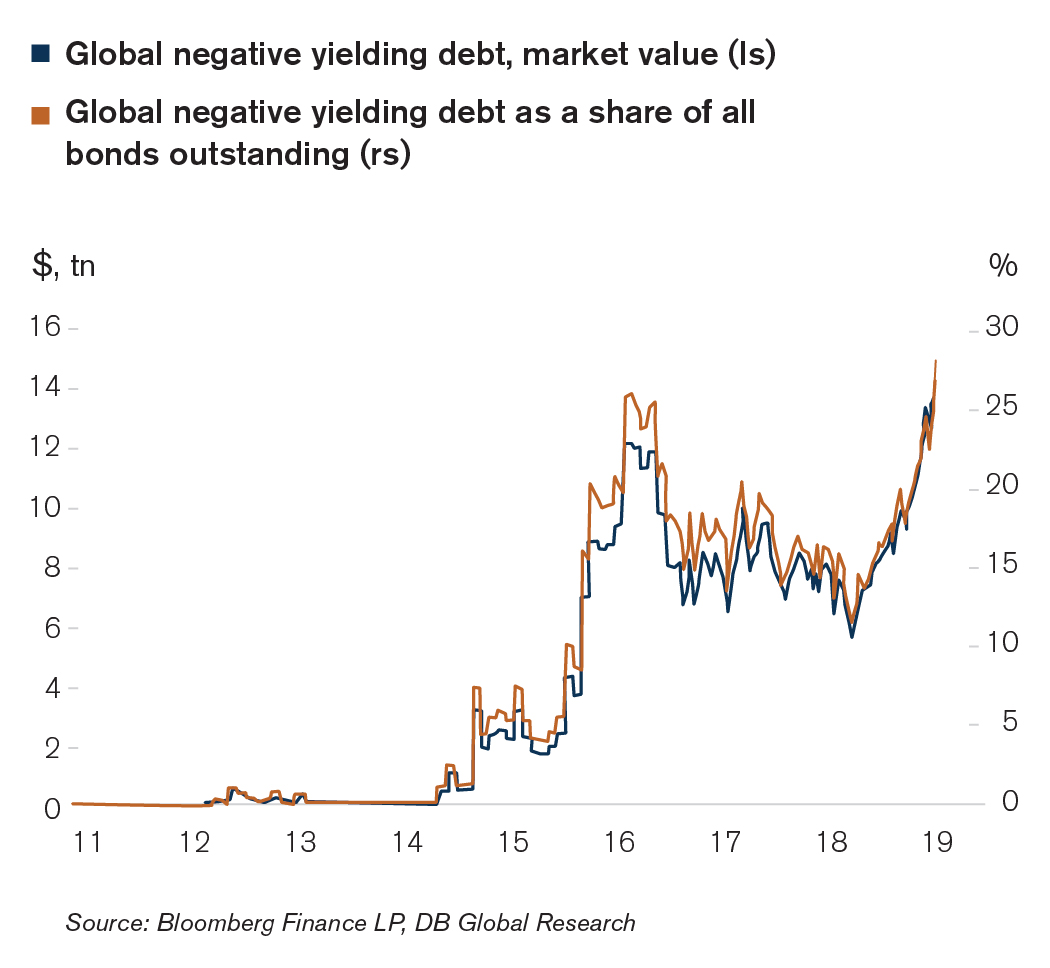

Yes, negative bond yields exist and in a big way! Deutsche Bank estimates that there are more than $15 trillion worth of negative-yielding bonds in the global market, representing 27% of all bonds outstanding.

Japan is the main culprit; but the problem also resides in Europe. In fact, collectively Japan, France, and Germany represent over 70% of negative yielding global debt (with the entire German yield curve currently below zero).

27% of bonds in the world trade at negative interest rates

Why does this exist and who would buy these bonds?

It all started in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Central Banks in Europe and in Asia pushed their short-term interest rates to zero in an effort to stimulate economic activity. The thinking was that by penalizing investors and banks for holding cash, they would be more inclined to do something with it. Businesses would invest, consumers would spend, and banks would lend. Unfortunately, it didn’t quite work. So, Central Banks then moved rates into negative territory – which also failed. Seeing no other option, they began to buy their own debt, pushing prices up and interest rates down, all in an unsuccessful attempt to provide economic stimulus. As they continued to keep at it, over time government bond yields moved lower and lower and eventually fell into negative territory—partly due to ongoing buying and partly due to falling inflation expectations amidst the slow pace of economic growth.

This tepid economic environment caused early investors to worry more about a return of their money rather than a return on their money—and they were comfortable with losing a little bit of value in order to keep their savings safe. Think of it in a different way—if you were to store your prize possessions (e.g., cars, art or jewelry) you would expect to pay a small fee to the holder in exchange for keeping your assets safe. Same holds true with your cash—at least if you are European or Japanese.

As more and more investors piled in, rates fell further into negative territory. Investors, in turn, began looking towards higher quality corporate bonds to secure a better yield. And as money began shifting into this sector, prices rose and yields fell until they too turned negative. Today, according to Deutsche Bank and Bloomberg, there is close to $1 trillion in negative yielding corporate bonds. Even some European High Yield bonds are trading with negative yields! Maybe it’s time to change the name back to junk bonds as high yield is certainly a misleading moniker these days.

No one, however, is upset yet because as yields become more and more negative, earlier investors keep winning due to falling yields driving prices higher. Consider our earlier example where a 5% coupon bond traded at $106 for a – 1% yield or $1 loss. Today, that investor might be able to sell their $106 bond for a higher price (perhaps $108); causing the next investor to face even worse negative yields. At some point though, a negative yield bond will ultimately have to offer negative returns.

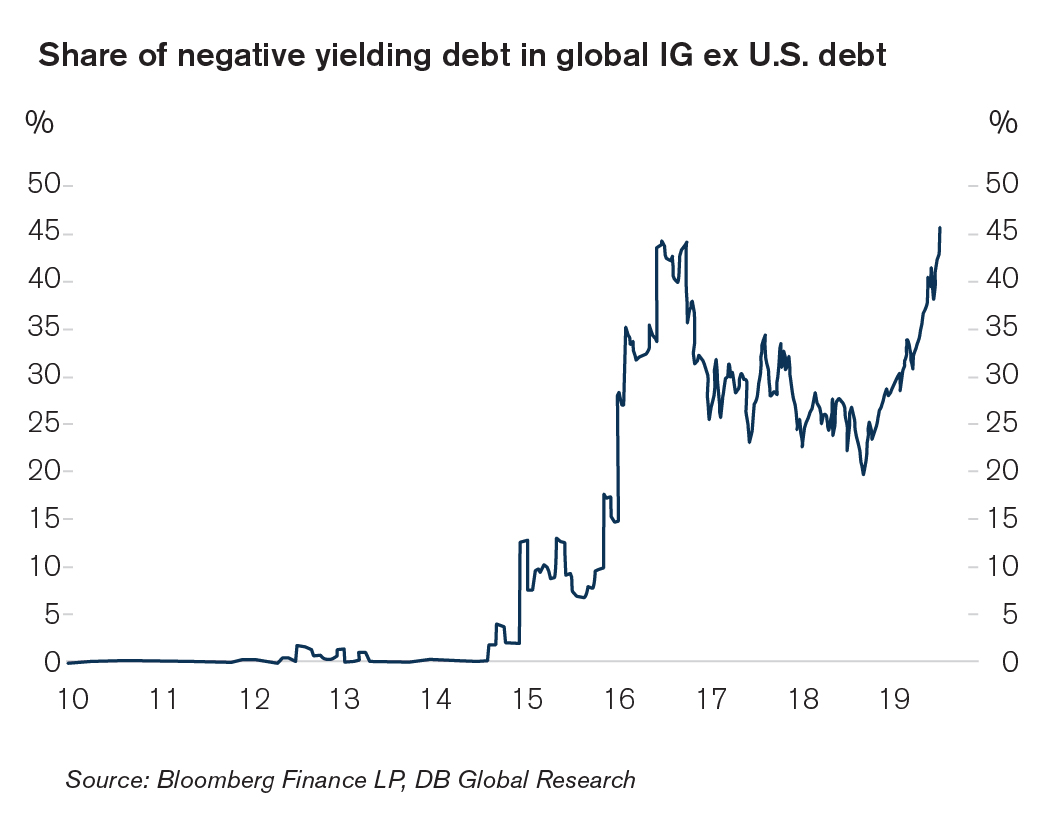

Excluding the U.S. from the global IG Index shows that 45% of global bond markets outside the U.S. trade at negative yields.

What about the U.S.?

The coronavirus and its negative effects on the global economy have influenced investors to sell risky assets (stocks) and rush into safer assets (U.S. Treasuries) pushing bond prices up and yields down. While U.S. rates are still positive, longer-term US Treasury bond yields have moved lower and are now at their lowest level in history with both the 10-Year (+1.32%) and the 30-year (+1.80%) breaking to new lows (as of February 25, 2020). While low, they are still greater than zero—but not after accounting for taxes and inflation so negative real yields is now at our shores. Will negative nominal yields be next?

It’s a possibility but the Federal Reserve has gone on record that they do not think it is a good idea. Well that’s certainly good news but there’s a different kind of “negative” problem investors need to worry about.

Less than Zero (Inverted Yield Curve)

Remember the earlier example of a longer loan earning less interest? That’s the case now in the U.S. as the yield on money markets is near 1.50% while the yield on the 5-year Treasury bond is near 1.14% (as well as the previously stated yield on the 10-year Treasury bond at 1.32%) This spread between shorter-dated bonds and longer-dated bonds (which is usually positive) is now less than zero – which in bond parlance is referred to as an inverted yield curve.

Schwab might have said it best: “not only should bond yields be positive, but longer-term bonds should have higher yields than short-term bonds—that’s a ‘normal’ yield curve. Investors usually demand a risk premium to compensate for tying up their money for a longer period of time.”

Why is this a problem? In short, an inverted yield curve often serves as a signal; suggesting good growth today, but lower growth in the coming years. Said another way, an inverted yield curve can be a harbinger of a looming recession.

What does it all mean?

While it’s true that a yield curve inversion has predicted the last 5 recessions (all data here is Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis), it’s also true that in each of those instances, the yield curve was inverted for an average of 503 days before the recession came to fruition. It is also true that in each of those 5 recessions, the Federal Reserve’s last interest rate hike either inverted the curve itself or came at a time while the curve was already inverted. But the 2019 curve inversion came three months after Jerome’s Powell’s last interest rate hike. In other words, the last hike this cycle came while the curve was still positively sloped (albeit a mere 30 bps or so) unlike prior recessions. Is it different this time? Perhaps.

Nevertheless, recession watch is at its highest level this cycle. And with the headwind of a global virus, the heightened volatility in quarters ahead is something to bear in mind when reviewing your financial plans for the next 24-36 months. The Investment Committee and Senior Advisors here are mindful of the potential risks and have been adjusting our recommendations in a thoughtful and rational manner while looking forward to a time when negative AND less than zero mean the same thing!

Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. Securities offered through Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advisory services offered through SIA, LLC. SIA, LLC is a subsidiary of SEIA, LLC, 2121 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600, Los Angeles, CA 90067, (310) 712-2323, and its investment advisory services are offered independent of Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. is separately owned and other entities and/or marketing names, products or services referenced here are independent of Royal Alliance Associates, Inc.