By Christine Sol

Investment Strategist

Executive Summary

- Back in April, serious concerns arose around municipal bonds as Mitch McConnell stated he was in favor of state bankruptcy, raising concerns about the financial health of municipal issuers and the willingness of government to provide unlimited support.

- Going into the global pandemic, states have historically low default rates, large rainy-day reserves, federal support, and the flexibility to tax and cut spending.

- Most municipalities will struggle with lost tax revenues, but in general are well equipped to survive the COVID-19 crisis.

- Selectivity remains critical for investors in the muni space, as clear winners and losers emerge from the 2020 recession.

On April 22, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell stated categorically that he favored allowing states to declare bankruptcy rather than providing them with a federal bailout. Fueling fears of possible state bankruptcies, the statement has generated a great deal of scrutiny into the safety and health of municipal bonds (munis).

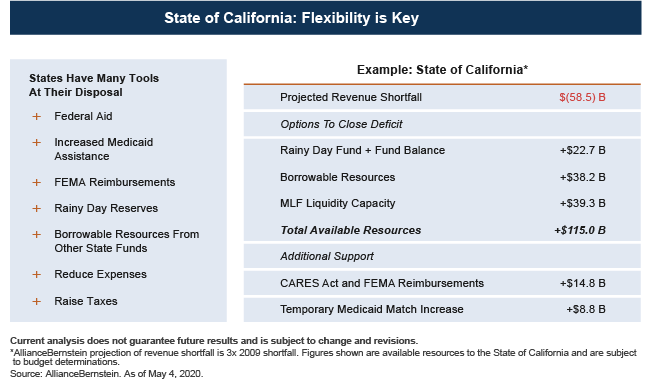

Rainy-day fund resilience

Because of their pivotal importance to communities, munis have a variety of tools at their disposal which have enabled them to weather previous external market shocks. At the start of 2020, most municipalities had record amounts of cash on reserve fueled by strong revenue growth over the past decade. In fact, most municipal issuers are financially stronger today than they were prior to the 2008 global financial crisis. States entered the COVID-19 crisis with rainy-day funds equal to $75B (the equivalent of 7.7% of annual spending). That amount is more than 1.6 times more than the rainy-day funds they held entering 2008. Additionally, states have options to balance their budgets, the ability to draw on reserves, sweep cash from additional funds, cut spending, raise taxes, and stretch payables.

Despite these levers, it’s certain that states will require some degree of federal funding to help offset the sharp drop in sales and income tax revenues they will face in the first half of the year. And there’s bipartisan support for aid to states in the next coronavirus bill – with both Democrat and Republican senators introducing bills that include state aid.

Furthermore, the federal government is already committed to supporting states (by both buying munis and providing direct aid). Backpedaling support now isn’t a politically viable strategy as it flies directly in the face of public opinion.

Context matters

It’s important to understand the context behind Senator McConnell’s statement. It was a direct reaction to Illinois State Senate President Don Harmon, who requested $41B in federal aid ($10B of which would be earmarked for the state’s underfunded pension fund). McConnell then went on to speak out against cutting federal blank checks to bail out state pensions. In an attempt to push back against state budget mismanagement, some took his words as a shot across the bow of state-run hospitals and medical centers (which are guaranteed support).

First, it is important to note that the current pandemic is a health issue; not a pension or state governance crisis. In its wake, many states will have significant budget deficits and large investment losses. Only three states (New Jersey, Illinois, and Kentucky), however, have pensions that are underfunded below 40%. And EVERY state has ample pension cash on hand to pay pensioners through this crisis and well beyond. Because they are long-term liabilities, underfunded pensions pose no immediate threat to municipal solvency.

Bankruptcy was never really on the table

Under the current Federal Bankruptcy code, states are prohibited from using Chapter 9. Allowing them to go bankrupt would not only require a new federal law, but state legislatures would also need to change their constitutions to give their governors the authority to seek bankruptcy protection. These are tremendous legislative hurdles that don’t have political support at any level of government.

It’s an idea that was also floated in the aftermath of the 2008 recession but quickly shot down by both Democrat and Republican governors. Even assuming a new precedent was somehow set, if any state filed for bankruptcy then investors would demand higher yields (regardless of the state’s creditworthiness) in order to compensate for the added risk. Why go down a path that could structurally change your future borrowing costs when other remedies are available?

During the Great Depression, Arkansas was the only state to default on its debt – and they recovered in 2 years and paid back their investors in full. Since the Great Depression, no state has ever defaulted despite numerous recessions, wars, and terrorist attacks. Why? Because states are monopolies that have sovereign powers and flexibility to raise revenues, cut expenses, delay payments, and share costs with lower levels of government. It’s hard to imagine how a state could even prove “insolvency” given their almost unlimited taxing power.

No danger of default

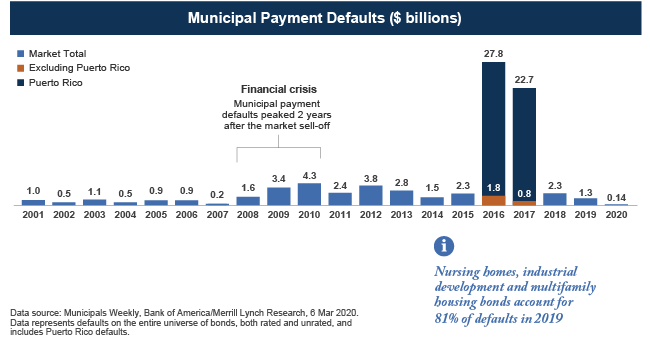

The average 5-year U.S. municipal default rate since 1970 has been just 0.16%. On average, states are not highly leveraged at all (debt service accounts for just 4.5% of state budgets). And well in advance of this current lockdown, several municipalities established a habit of hoarding cash.

- Airports: Many airports hold over a year’s worth of cash: LAS has over 900 days’ worth of cash on hand, SAN has 750 days, LAX has over 500 days, SEA-TAC has 530 days, and SFO has 350 days’ worth of cash on hand. Also, the Federal stimulus package gave airports an additional $10B – more than enough to cover their $8B in debt service for the entire year.

- Toll roads: The same goes for toll roads & mass transit systems. The Bay Area Transit Authority has 2000 days’ worth of cash on hand. The Foothill Eastern Corridor has 5600 days’ worth of cash earmarked for discretionary capital projects which have now been halted. And the South Bay Expressway has over 180 days of cash on hand.

- Health Care: Hospitals are on the front lines and local, state, and federal governments will not let them fail. Presently, hospitals are set to receive $200B in aid with more to come. For many hospitals, elective surgeries are coming back sooner than expected, and Medicare guidelines are being updated to allow for telemedicine and other no-contact services.

- Water/Sewer/Power: As monopolistic services with cash reserves and the ability to set/adjust rates and pass down costs, these essential service providers will not be impacted by COVID-19.

Of course, there will be significant revenue shortfalls. But most states are projected to break even through a combination of aid and savings. Outside of Illinois, New Jersey, and Kentucky, the message from most experts in the muni space is that the coronavirus is a liquidity issue, not a credit issue. And the Fed’s municipal liquidity facility ensures that no municipality can be shut out of the market. States can go directly to the Fed, if needed, to borrow funds to fill their liquidity gaps.

A closer look at municipal financial fitness

As of the end of February, California had a strong and healthy balance sheet: roughly $17.5B in general fund reserves (about 12% of revenues) and available liquidity of about $47B. Public debt as a percent of gross state product (<3%) was at its lowest level in years, with no short-term debt outstanding. This liquidity should allow the state to deal with near-term revenue shortfalls (including a 3-month delay in the 2019 tax return filing deadline). According to Moody’s, even if the state didn’t collect ANY revenue in the final quarter of the fiscal year, California would still end the fiscal year with about $9B in available liquidity.

As a secondary line of defense, the state also has the ability to defer payments in areas like schools or higher education, to cut-back certain services, and/or raise taxes (possibly on a temporary basis). While the state hasn’t yet announced its revised budget and revenue shortfall, even factoring in a worst-case scenario of a $50B shortfall, with the tools and cash reserves on hand (on top of any expense cuts that will occur) California is in no danger of default.

Additionally, the CARES Act provides significant aid for both the state and local governments, including:

- California will receive $15.3B in aid, with $8.5B going directly to the state itself and $6.8B going to cities and counties with populations of at least 500,000 people to help offset COVID-19 related costs;

- $3.7B in education stabilization funds to be evenly split between higher and elementary education;

- $1.5B to $2.5B of extra federal Medicaid funds through a higher match;

- California hospitals will receive a portion of the $100B in CARES Act aid that’s earmarked to help offset costs and to replace lost revenues due to COVID-19; and

- LAX and SFO are projected to receive $266M and $212M respectively (nearly 20% of their annual revenues).

At the state level, Virginia municipal bonds are solidly AAA-rated due to the state’s conservative fiscal management, stable economy, and relatively low debt burden. Heading into 2020, Virginia maintained a constitutionally supported Revenue Stabilization Fund (only to be used in the event of a revenue shortfall) worth $1.6B. Government employment represents 18.1% of Virginia’s job base (compared to the national average of 15.2%). Per capita income is 116% of the U.S. average, and the state’s March unemployment rate of 3.3% and poverty rate of 12% were both below the national averages. Due to strong employment demographics, Virginia’s balance sheet has greatly benefitted from a decade of revenue growth, a $4.2B rainy-day fund, and a stable worker base.

Virginia will receive $8B in direct federal aid; 70% of which has been earmarked for essential services such as education and transportation. Despite prudent fiscal management, in a special budget session, Virginia will re-forecast the budget and will plan to cut funding to universities, halt approved construction projects, lower lotto payouts, and propose short-term borrowing up to $500M for the state and $250M for localities to cover any cash flow issues. The largest sector of Virginia municipal debt is transportation – primarily supported by airport and toll road revenues. This is certainly a revenue headwind, but like California, Virginia’s airports will be supported. IAD and DCA will receive $143M and $86M respectively.

On the legislative front, the Governor of Virginia has frozen new spending in the state budget, delayed an increase in the minimum wage, and will call a special budget session to reevaluate and reconsider what the state can afford and where it can allocate funds. In light of all these actions, Virginia looks well-poised to weather the COVID-19 storm without the threat of default.

Challenges ahead, but still a worthy portfolio building block

Over the past decade, states have painstakingly amassed rainy-day funds for emergencies like this and many municipalities currently offer some of the safest credits available to investors. It is projected that these rainy-day funds and $150B in committed aid will be ample cash for states to replace the tax revenue lost from the shutdown. The municipal credit market has proven to be resilient through different exogenous shocks and market crises.

Even so, there are challenges ahead as governors must grapple with the certainty of raising taxes and deep budget cuts. The re-opening of state economies will help to relieve some of the pressures on cash flow, but states will not be out of the woods yet. Already, rating agencies have downgraded issuers with a strong dependence on tourism and oil revenues and have placed several municipalities on negative outlook. We believe that downgrade risk, not default risk, will be a bigger influence in the municipal market in the near-term. Markets will continue to react to headlines, but municipal bonds have historically been resilient and are fundamentally strong. There are some parts of municipal credit that are less vulnerable than others, but the notion of state bankruptcy is far from reality and the path for recovery for municipal credit is more clear than other types of credit. Despite inevitable challenges and obstacles that will arise as we slowly bring our nation back online, the financial health of both the national and state economies bodes well for the long-term prospects of the municipal bond market.

The information here was obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, it cannot be guaranteed. In general, the bond market is volatile. Municipal bond offerings are subject to availability and change in price. If sold prior to maturity, municipal bonds may be subject to market and interest rate risk. Bond values will decline as interest rates rise. Depending upon the municipal bond offered, alternative minimum tax and state/local taxes could apply. Municipal bonds may not be suitable for all investors. Please see your tax professional prior to investing. Securities offered through Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advisory services offered through SIA, LLC. SIA, LLC is a subsidiary of SEIA, LLC, 2121 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600, Los Angeles, CA 90067, (310) 712-2323, and its investment advisory services are offered independent of Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. Royal Alliance Associates, Inc. is separately owned and other entities and/or marketing names, products or services referenced here are independent of Royal Alliance Associates, Inc.